This guide is for those who have no idea how to reference. However, I have no doubt there will be third and fourth year students refreshing their memories on the ins and outs of when and how to cite and reference. This blog entry is intended as a first draft of an instructional video appearing on the Thinking Aloud Youtube channel.

The best thing you can do for if you’re here a refresher is to head over to Anglia Ruskin University’s library web page on the Harvard system. It’s excellent and has been an essential tool for undergraduates and postgraduates since, at least, 2008 (When I remember first using it as an undergrad at Strathclyde). The best thing about it is when you need to know how to cite a more irregular source it tells you what the citation and reference should look like. Load up the page, link is below, and bookmark it. You won’t regret it. Frankly, now I’ve given you this advice and I will repeat it in class too, I expect your referencing to be on point or damn close to it.

This blog covers:

- Why you need to cite and reference

- The difference between citations and references

- When to cite

- How to cite

- How to reference

Why you need to cite and reference

- Displays where your ideas came from

- Demonstrates the quality of your reading

- Demonstrates the amount of research conducted

- Protects against plagiarism

Every marker wants to know where your ideas came from. The first thing a marker does is scrutinize the reference list. We want to know what reading you’ve elected to use for your argument. The best thing a marker hopes for is to find a reference list full of academic journal articles capable of teasing apart the intricacies of the assignment. Academic references are king, that means journal articles, books and textbooks, not websites and blogs. If your marker checks your reference list and is confronted by, to be polite, subpar references, you’ve already limited how good the mark can be. The volume and variety of research is very important. Students often ask what the magic number of academic references is… there isn’t one. You could have 30 references providing shallow opinions or 10 references conducting deep analysis. The word limit should help guide the trade-off between quality and quantity. Protection from plagiarism. You are acknowledging other’s work and please, burn this into your brain: Every source you use incorporating others’ work requires citation. No citation declares your writing as original. Therefore, if something goes uncited and it’s not original then you’ve plagiarised. Now, there’s obviously degrees to how badly something can be plagiarised. It needs to be blatant, e.g. outright copying, for more severe consequences, i.e. expulsion. So, there you have it. Every time you think, “Why do I have to do this referencing rubbish?” and the tawdry answer of “Because I say so” isn’t good enough, remember:

- Referencing displays where your ideas came from

- Referencing demonstrates the quality of your reading

- Referencing demonstrates the amount of research conducted

- Referencing protects against plagiarism

I won’t get caught

Now, you could be forgiven for thinking “How does the reader know I’ve copied?”. They’d need to have read everything I’ve drawn upon (a marvellous feat in the internet age) and possess a photographic memory. However… Turnitin has read everything you’ve read and it possesses a photographic memory. Every assignment submitted electronically at most universities, is compiled in their database and is systematically cross-checked. Copying from other students counts, remember, their work is uploaded to Turnitin too. TLDR: you will be caught. Don’t do it.

The difference between citations and references

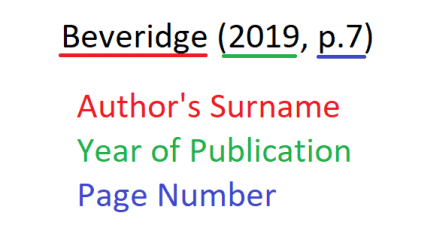

You may have noticed the terms ‘citing’ and ‘referencing’ are often used interchangeably, as if they were the same thing. They’re not. And the reason they are equated is laziness. The primary difference is citations are shorthand and occur in the written text whereas references are compiled arranged in a list after the written work and written longform, i.e. cover page>essay>reference list.

Citations signal external information you’ve consulted and is displayed in the appropriate short-hand form. Each citation has a corresponding reference. Individual references comprise the reference list, each containing all the relevant information for the reader to access the original material you consulted. It’s a system for transparency.

When do I cite?

Every time you use someone else’s idea. So, whenever you:

- Quote

- Paraphrase

- Borrow a theoretical model

- Borrow an idea/concept

- Explicitly refer to another’s work

Quoting, i.e. when using a definition or perhaps critiquing an established definition. Paraphrasing, i.e. you know that paragraph you just read? You thought it was good but you can’t copy it. So, you thought I’ll just paraphrase it and fold it in. That needs cited. It’s plagiarism if you don’t. Assignments are often best answered using theoretical models to explain the intricacies of phenomena. Assignments may even ask you to critique specific models. You need to cite those models, preferably from the source material and not lecture slides in which it was first encountered. Some academic ideas do not have explanatory models but are supported by more exploratory ideas or concepts. They too require citation. Other works, possibly, seminal works or literary works should also be cited.

How to Cite

This is a bulky section but it’s the most important. I’ve chosen examples from my Ph.D. thesis. I go through the most common types of reference and the reason for their choosing. I’ve used my thesis out of convenience.

Author’s name in text

- Dowling and Pfeffer (1975) observe CSR and charitable donations are a, context specific, form of legitimising behaviour.

- Suchman (1995) views legitimacy as a process and Deephouse (1996) sees it as a state. Framing legitimacy as a state lends itself to measurement but diminished nuance, whereas, Suchman accommodates for change, conceptualising the implications of production, consumption, and activity.

Example 1 is standard example citing an author’s name in text. Example 2 uses two author’s name in text citations in one sentence. It’s useful in this context as it allows the author to distinguish between two thinkers on legitimacy. This demonstrates reading but also the implications of endorsing one perspective over the other.

Author’s name not in text

- Organisations operate as part of a ‘superordinate social system’ in which the utilisation of resources, in light of the relative opportunity cost, affords some degree of legitimacy while goals resonate with society at large (Parsons, 1956).

This example paraphrases Parsons and opts to include his name in text. This decision is due to paraphrasing and a personal preference to preserve narrative flow.

Quotation with author’s name in text

- Suchman (1995, p. 574) defines legitimacy as: the “generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs and definitions”.

This is a definition. Definitions must be quoted, and all quotes require page numbers.

Quotation with author’s name not in text

- ‘Older sociology… tended to rest on the idea that deviance leads to social control. I have come to believe the reverse idea, i.e., social control leads to deviance’ (Lemert, 1967, p. v).

An assertion on the nature of discussed phenomena. Similar in purpose to using a definition. Author’s name is not included to preserve the narrative flow, it is a hanging quote at the beginning of a section to frame the premise of the argument.

Two authors in text

- DiMaggio and Powell (1983) observed that institutionalised organisations were becoming increasingly homogeneous; pushed into alignment with prevailing institutional ideals by a process called isomorphism.

This is how you include a citation with two authors. It’s the same as a citation with one author. The only difference is two people wrote it.

Two authors not in text

- Maintaining and acquiring legitimacy can prove difficult irrespective of past perceptions of organizational activity (Armstrong & Abel, 2000; Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978).

This demonstrates two sources of two authors not in text. This example is useful because it reports agreement on a specific aspect of legitimacy from two sources. If more sources agree on this specific issue (and they probably do) it’s acceptable to include them also.

Three, or more, authors in text

- It is worth observing Mitzberg et al’s (2009) miscomprehension on the existence of choice, neo-institutionalists do not claim choice does not exist but instead insist choice is restricted based upon external factors. The greater the restriction the more complicated institutionalists perceive the environment to be.

Here’s an example some find confusing. So, three authors is written most frequently as the name of the first author and the rest abbreviated to et al. Mintzberg et al means Mintzberg and others, with et al being Latin. Hence the use of italics. Sometimes you will see the full citation written out including all names. Those who do this will only do so for the first time the citation is included. Each time thereafter will use et al.

Three, or more, authors not in text

- Acquiring legitimacy “is a contested process that unfolds through time” (Johnson et al., 2006, p.59) via implicit and explicit processes.

This functions the same way as citing three or more authors. The example shows you a definition, hence the need to quote, and the appropriate page number.

Combinations

- In modern management writing, one of the earliest definitions of an institution comes from Hughes (1936, p.180): “The only idea common to all usages of the term ‘institution’ is… some sort of establishment of relative permanence of a distinctly social sort”. Understandings of institutions are not confined to management literature but are also explored in economics, political science and sociology. There is consensus amongst social scientists that institutions exist but there is more agreement on what institutions are not rather than what they are (DiMaggio & Powell, 1991). Due to embedded ontological assumptions, which will become apparent in the upcoming section, this thesis adopts the neo-institutional perspective (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983; Meyer and Rowan, 1977) but those wishing to learn more on differences – although attention is given when necessary – between the perspectives should consult Scott (1987).

This example shows several of the citations discussed combined as part of a coherent paragraph. The more practiced you become in citing correctly the more natural this process becomes. Any journal article or academic text you consult will provide you with examples of this.

There are many more ways of citing dependant on the source material, e.g. websites, industry reports, government white papers, to name a few. If I were to cover all examples you would fall asleep. I’m not trying to bore you; I’m trying to give you necessary knowledge. So, with this in mind, I direct you to the aforementioned Anglia Ruskin University Library website on Harvard referencing. It is indispensable.

How to Reference

The reference list includes the full details of every source cited in the assignment. Citations are short-hand acknowledgments whereas the reference list includes the source materials full details. This allows the marker to inspect the validity, reliability, and quality of your sources. If the information included is insufficient to do so then no credit can be given for that part of the argument.

As I have done for the How to Cite section, I will provide examples of full references for the following sources: journal articles, textbook, edited books, chapters of edited books, websites, and online newspaper articles. I’ve selected these as, in my experience, they are the most common types of reference.

Journal article

The formula – Author(s). (Year of publication), title of article, title of the journal containing the article, journal volume number (journal issue number), the page numbers of the article within the journal.

Here are two examples. One with more than three authors and one solo author:

Alexander, M.J., Beveridge, E., MacLaren, A.C., & O’Gorman, K.D. (2014). “Responsible drinkers create all the atmosphere of a mortuary”: Policy implementation of responsible drinking in Scotland”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 26 (1), pp.18-34.

Suchman, M.C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571-610.

Textbook

The formula – Author(s). (Year of publication). Title of book, location of publisher: name of publisher.

Hall, S., Critcher, C., Jefferson, T., Clark, J., & Roberts, B. (1978). Policing the Crisis. Mugging, the State, and Law and Order. London: MacMillan Press.

Parsons, T. (1956). Structure and Process in Modern Societies. New York: Free Press.

The titles of books are italicised because it’s the name of a publication.

Edited Book

The formula – Author(s), ed or eds. (Year of publication). Title of publication, location of publisher, name of publisher.

Powell, W.W., & DiMaggio, P.J. eds. (1991). The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Chapter of an Edited Book

The formula – Author(s). (Year of publication). Title of chapter. In (name of the editors) (eds), title of book, location of publisher, name of publisher.

Beveridge, E. & O’Gorman, K.D. (2012). The Crusades, the Knights Templar and Hospitaller: a combination of religion, war, pilgrimage and tourism enablers. In R. Butler & W. Suntikul (eds), Tourism and War: A Complex Relationship. Contemporary Geographies of Leisure, Tourism and Mobility, London.

DiMaggio, P.J., & Powell, W.W. (1991). Introduction. In W.W. Powell and P.J. DiMaggio (eds.), The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Website

The formula – Author(s) or Source name. (Year of publication). Title of web page, (date updated, if any), Available at: Insert web address.

NHS Inform. (2019). MMR Vaccine, [online], (Updated on 23/08/19), Available at: https://www.nhsinform.scot/healthy-living/immunisation/vaccines/mmr-vaccine

Scotch Whisky Association. (2019). Scottish Parliament raises a glass to 525 years of Scotch Whisky, [online], Available at: https://www.scotch-whisky.org.uk/newsroom/scottish-parliament-raises-a-glass-to-525-years-of-scotch-whisky/

Online Newspaper Article

The formula – Author or Name of newspaper/publisher. (Year of publication). Title of article or page, name of newspaper/publisher, date of publication. Available at: URL

Duell, M. & English. R. (2019). Meghan Markle flies COMMERCIAL! Duchess leaves four-month-old Archie at home for two-day trip to New York on public flight to watch her friend Serena Williams play in US Open in wake of private jet storm, Mail Online, [article] 06/09/19. Available at: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-7434713/Meghan-jets-New-York-watch-friend-Serena-Williams-play.html

Kijewski, L. (2019). US woman charged with trying to smuggle baby out of Philippines, The Guardian Online, [article] 06/09/19. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/sep/05/american-philippines-baby-human-trafficking-charge

A few final words

This may seem a little overwhelming, but if you just get your hands dirty and begin to learn the ins and outs through practice, you’ll do fine. Here are a few final bits of advice.

Consistency

Be consistent. When comparing sources, you’ll find small differences. Some references use a full stop where others use a comma. Some include the authors first name instead of an initial. Others may include the ‘Vol.’ abbreviation before including the journal volume number. What’s important for you is to pick one of these and stick to it. Chances are your marker will only take issue with it of you have discrepancies within your work, i.e. two different formats for writing a journal reference. Keep it all the same. Be consistent.

Reference list not bibliography

This makes my head want to explode. Reference lists and bibliographies are not the same. Every single year students act like they are, despite persistent cajoling to the contrary. A reference list is every source cited in the written work. A bibliography is every piece of reading which may have influenced your writing. Bibliographies have no place in task-oriented university assignments. Reference list not bibliography.

Include Everything

If you cite a source, you must include it. If you don’t include a corresponding reference for your citation no marks will be awarded for those sections. Include everything.

Presentation

This is linked to be consistent. Presentation is a massive deal. When the marker flicks straight to the reference list and finds a disordered mess waiting on them. They will immediately start taking notes of all the mistakes. If you take care of presentation and be consistent, it’ll go a long way to help maintain good standards in your refencing.

Software and websites

This has the potential to be beneficial and enormously detrimental. Endnote is an excellent piece of software (Available to Strathclyde University Students via the library.) and a great boon for citing and referencing assignments. However, the software is only as good as the user. If the software is not properly set up and, most importantly, you don’t know what the outputs are supposed to look like then its useless to you. The bottom line is you need to know how to reference first before you start using this software. Websites *audible sigh*… over the last few years there’s been a rash of students using Citethisforme and perhaps other similar websites. I don’t mean only first years, third and fourth years too. Students who should know better. The references it gives you are wrong. Not a little wrong but horribly wrong and the presentation of them is garbage. Do not use these sites to do your work for you. You will receive zero credit for this significant portion of your assignment if you do this. Markers will know you’ve done this immediately and you will come off as someone who doesn’t care about their work. Avoid rubbish websites. Endnote is excellent but its only as good as the information it receives and operated by someone who knows what referencing and citing is supposed to look like.

Fin.

That’s us finished. For those new to this, I hope you’ve learned a few things about what to do and what to avoid. For those refreshing, I hope you’ve found what you needed. If not, please leave a comment with any specific questions. Remember, when in doubt, consult and bookmark the Anglia Ruskin University Library page on Harvard referencing. It’ll keep you on the straight and narrow. Best of luck in your assignments.