Why I Think Storytelling is Great for Learning

I think storytelling is great for learning for two reasons. I think human beings are hard-wired to learn this way; and stories can impart specific lessons with room for post-telling reflection.

Hard Wired

I find it hard to disagree with my assertion that human beings are hard-wired to learn via oral exchange, i.e. speech and storytelling. Human beings (homo sapiens) have been around for roughly 350,000 years. However, it didn’t take long to develop sophisticated language, with the origin of speech estimated during, the very large window, of 350,000 to 150,000 years ago. Let’s be as stingy as possible and assume our species has been speaking for 150,000 years.

We don’t think of writing as technology. Our minds consider steam power, electricity, automation, A.I., digitisation as the fruits of technological revolutions. Writing is a singularly important technological revolution for our species. The earliest examples of writing are called ‘proto-writing’, using symbols and images, to convey a restricted number of ideas unlike writing which specifically communicated the language of the author. Cuneiform of Ancient Sumeria is one of the oldest (3,400 BC), then hieroglyphics of Ancient Egypt (3,100 BC), and the Xia Dynasty China (2,000 BC). There are some older examples, like the Indus and Rogongo scripts dated around 5,500 BC, but whether they can be classified as proto-writing is debated by academics. Actual writing, the accurate communication of spoken language in written form was in the Near East around 2,600 BC. This technology emerged as civilisations expanded enough to require treaties, trade agreements, peace agreements, recorded history, commercial arrangements, etc. It played a significant role in civilising the world. Civilisations existed across the globe at this point. The dissemination and implementation of writing didn’t occur simultaneously across all cultures. Many places didn’t adopt writing for many centuries. Take Scotland, my home, as an example. Scotland adopted writing, in Latin, between 600-700 AD after the decline of the Roman Empire due to the zeal of Christian Missionaries. Knowledge of older civilisations in Scotland is scarce due to a lack of written records.

Bearing this in mind, I will for the purpose of my own argument take the smallest window possible to illustrate my point. So, we’ve been able to speak for 150,000 years. It’s been 4,600 years since the implementation of recognisable language in the Near East. That means human beings had 145,000 years of communicating, speaking, teaching, preserving history and tradition, without writing. It’s a long time and it’s why I think we can underestimate the value of learning done via oral communication.

Lessons

I think storytelling is undervalued in the classroom, and when I say ‘classroom’ I’m including lecture theatre and tutorial seminar. Civilisations’ preserved oral histories and traditions for 150,000 years as a means of providing lessons for future generations, preserving culture and identity but also to prevent future generations from repeating mistakes. The best legacy of this are the rich myths, fables and parables that have emerged across the globe. Some educators already use the storytelling approach but call it something else, e.g. using case studies. Case studies tell a story, offering contextual richness for students and academics to explore, hang theory on, and facilitate analysis. Historical case studies are an exceptional teaching tool because it forces students to think beyond the immediate information and do further reading on macro-environmental forces impacting decision making. A good example is the Harvard Case using Singer (Sewing Machine manufacturer), one of the first multinational corporations growing across America, UK, Germany and Russia against the backdrop of two world wars. Complex situations affecting actors’ decision making is key to deriving understanding and meaning. This case study is a compilation of stories, key individuals who furthered the success of the organisation. Protagonists within the Singer Saga. Using stories, classic, modern literature and even film, offers many opportunities for exploring academic literature, in my case, business and sociological literature.

The value of stories, myths, fables and parables are the lessons they impart. There is always an intended lesson to be learned but there may also be additional layers which are not initially apparent. Something later realised after pondering. The lesson is often a moral one, one that defies the primal urges of our mammalian natures. Some examples include:

(Balthasar van Cortbemde’s Parable of the Good Samaritan)

The Good Samaritan. This parable, told by Jesus if Luke’s gospel is to be believed, can be interpreted in different ways. I’ll use the ethical one as the allegorical reading is more appropriate for those debating religious semantics. Jesus’s audience during the telling were Jews. At this point in time Jews hated Samaritans and vice versa due to an older conflict between the warring tribes. The Jewish traveller in the story is beset, robbed, beaten and dumped by the side of the road by brigands. He pleads for help from Jewish passers-by, but they won’t hear his pleas. When all hope is lost it is a Samaritan who stops and shows compassion. The last person any of his audience would have thought would aid the Jewish traveller, the person in the story whom his audience would identify with most. The deeper lesson would be to then reverse the roles, so literally, if a Jewish traveller discovers a Samaritan in need of help then he should do so, more abstractly, the lesson is to provide help to those who need it no matter how different they are from you.

(Rembrandt’s Return of the Prodigal Son)

The Prodigal Son. Another parable from Luke’s gospel, tells the story of two sons. One patient and dedicated with a sense of duty; and another who wishes to pursue pleasure and excess with no real thought beyond that. The prodigal son demands his inheritance early and blows it all, ending up an indentured servant when the money runs out. He returns to his father, contrite for his foolish actions and wishes forgiveness but expects none. His father grants him forgiveness and welcomes him into the family home once again. This comes as a surprise to both sons. The prodigal because he is genuinely ashamed of his wastefulness but also the eldest son who stayed. He feels spurned because his youngest brother, to his mind, deserves rejection as punishment. The parable is one about redemption and reformation. That we should grant forgiveness and opportunity for those who admit to wrongdoing when making amends. Not only should we do this but we must also try and do so without resentment. Interestingly, there is a similar Buddhist parable predating Luke’s gospel, indicating a much older history to the parable.

(Francis Barlow’s The Boy Who Cried Wolf)

The Boy Who Cried Wolf. Often thought of as a Biblical tale. It was certainly taught to me in religious education classes as a child but it comes from the Greek storyteller Aesop around 600 B.C. As we mentioned earlier, the story is likely much older. This fable, and fables are distinct from parables, has a shepherd boy lampoon local villagers about a wolf attacking their flock of sheep. There is no wolf and different stories provide a different motivation for the boy carrying out his trick. It’s most often for his own amusement. He does it a number of times, not tiring of the panic when everyone thinks the big nasty wolf has arrived. The point is he does it so often that when a wolf does come no one believes. He sounds the alarm and no-one comes. Some sheep, maybe even the whole flock, are killed. In some versions even the shepherd boy is killed. The moral being don’t tell lies. With the further caution that the more lies you tell the less people will believe you. The young boy in the story is convenient for parents’ to chide children about telling tall tales. We even have the English phrase warning against “Crying wolf”.

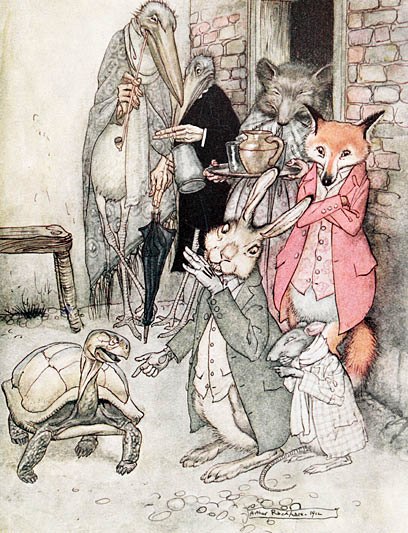

(Arthur Rackham’s The Tortoise and the Hare)

The Tortoise and the Hare. Another of Aesop’s fables. This is quite interesting, especially given my point about the usefulness of stories stemming from later reflection. The English phrase of “Slow and steady wins the race” is often attributed to this fable. The fable involves a hare ridiculing a tortoise for how slow he is. The tortoise endures it for a while but hates the embarrassment in front of the other animals. He decides he’s had enough and challenges the hare to a race. To all onlookers it appears absurd as a hare is much faster than a tortoise. They race and the hare speeds off. He gets so far ahead that he decides he can have a nap. He oversleeps and the tortoise overtakes him and wins the race. So “Slow and steady wins the race”. You could even think it’s about the importance of standing up to bullies. I don’t think it is. This story, true to Aesop’s Greek heritage, is about hubris. This is a warning against pride. The hare, who should’ve won this race hands down, is beaten by someone who had no business being in a race with him in the first place and it is entirely his own fault he lost.

Not just for kids

Now, the common theme here is that all of these four stories are used to teach children. I would forgive you for point out to me that I teach adults. In fact, you could take it further and say, you teach business subjects to adults at university. Why are childrens’ stories at all relevant to this? You are missing my point if this is your question. Storytelling is the methodology, the content of the story is for the teacher/tutor/lecturer to decide. Colourful characters, adventure, romance, monsters, magic, heroism, exotic locations, gods and goddesses may attract children but it attracts adults too. It is the storytellers job to reinforce the intended lesson underneath those colourful trappings. It may even require outright exposition but, as per my initial hypothesis, I think we are hard-wired to learn this way and it reinforces learning. As per my second hypothesis, it will provide intended instruction but it will also prompt later reflection. Greek tragedies are wonderful in this regard, as the tragic act itself is often a result of some basic human failing and demand answers. Answers we can never fully provide.

“Why did Icarus not listen to Daedalus?” “Why did Orpheus not ignore Eurydice for another five minutes? They were almost free.” “Why did Midas hug his daughter?” “How could Theseus forget to change his sails from black to white?”

Always with the Questions

This is the important bit. Questioning. In my experience, I’ve conducted a successful lecture when a student comes to ask a question afterwards. The question tends to come, whether consciously or not, from a philosophically critical perspective. Why? In a lecture there is little opportunity to ask questions. A tutorial allows open questioning. So, during the lecture the student hears the information and it pricks them. There’s something about it that doesn’t sit right and they wrestle with it internally throughout the class. The lecture finishes and they come to you with their question. Best example I have of this was during a lecture I provided on the philosophy of hospitality. Without going into too much detail, I asserted that altruism doesn’t exist. There’s no such thing as a selfless act. Every action a human can perform is transactional because even the satisfaction one takes from a charitable act is not selfless. The person receives satisfaction in exchange for their money or time, whichever it may be. The conversation went on for a while. The student even followed me back to my office with more questions about it, they suggested books I might like and he wanted reading h to learn more. These moments make education meaningful. This young man held something to be true and this conviction was fundamentally challenged. Irrespective of whether altruism is real or not, that process of critically examining our core ontological beliefs is fundamental to intellectual development. We never stop learning and I plan on folding storytelling into my teaching repertoire.

Pretty! This has been an extremely wonderful post.

Many thanks for providing this information.

LikeLike

I was suggested this website by my cousin. I am now not sure whether or not this put up is written by him as nobody else know such special about my difficulty.

You are amazing! Thank you!

LikeLike